- Lifetime Solutions

VPS SSD:

Lifetime Hosting:

- VPS Locations

- Managed Services

- Support

- WP Plugins

- Concept

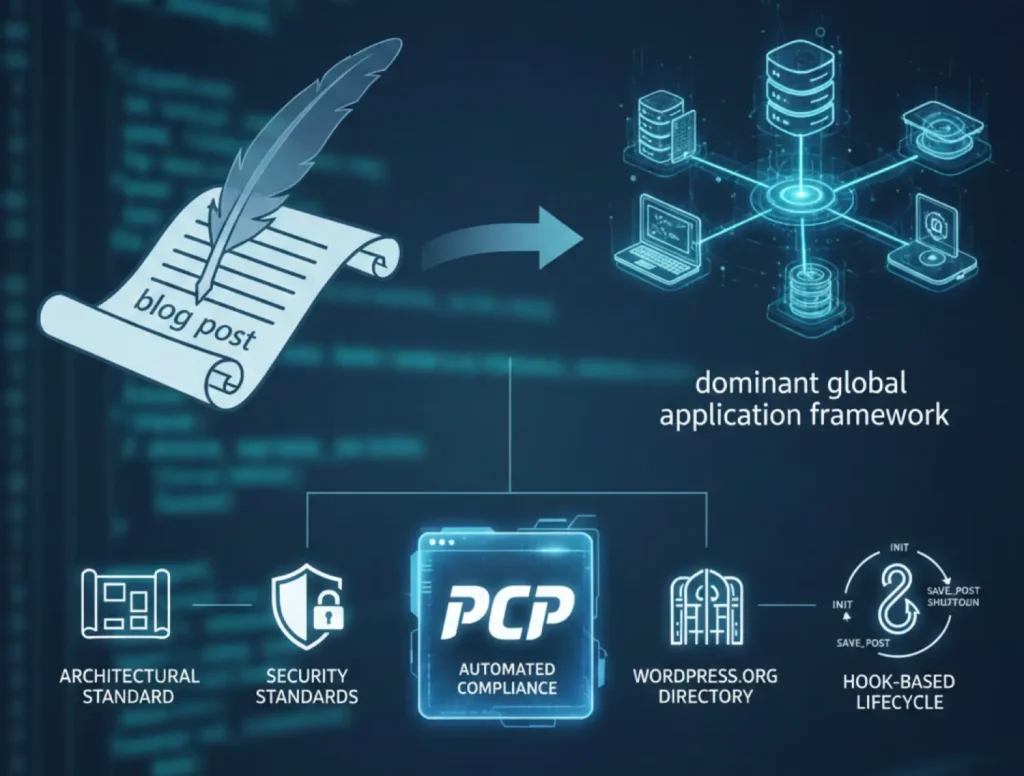

The evolution of the WordPress content management system from a fundamental blogging engine to a dominant global application framework has necessitated a parallel evolution in the standards governing its extensibility. A WordPress plugin is defined as a discrete software package designed to extend or augment the core functionality of the platform without modifying the foundational source code, thereby preserving the integrity of the system through core updates. The shift between functional scripting and professional authorship as a Plugin writer is a process of having to go through the architectural standard, strict security standards and the progressively more stringent gatekeeping of the WordPress.org Plugin Directory. In the contemporary world, the development of plugins is no longer a typical practice of logic in PHP but rather a field to which the rules of automated compliance frameworks, namely the Plugin Check Plugin (PCP), and strong knowledge of the hook-based lifecycle that constitutes the WordPress world should be adhered.

Creation of a WordPress plugin starts with its requirements and identification of a distinct identity. The first step is to establish the core features of the given plugin and the entry point into the existing ecosystem. A name should not only be unique so that the user can identify the name, but also the name should not create architectural clashes in the global PHP namespace. Due to the fact that WordPress loads all plugins in parallel, the chances of a name collision, where two different plugins come to define a function, a class or a global variable with the same name, are extremely high, with fatal errors frequently occurring and potentially impacting the operation of an entire website.

In order to counter these threats, the developers have to introduce a distinctive prefix to all globally available code. The prefix must preferably be four or five characters in length and differentiated from common English words or general terms. A choice of a plugin name is also a regulatory issue, as the WordPress.org Plugin Directory does not allow names that violate a trademark or a name that can be described using too broad and generic terms and potentially confuse the user. The inclusion of the Plugin Check Plugin (PCP) has added an AI-based tool, the Plugin Namer, which is available in the administrative interface and estimates the suggested names against existing entries in the directory and the availability of known trademarks before even a submission is created.

Every WordPress plugin must contain a primary entry point, typically a PHP file named to match the plugin’s unique directory slug. This main file serves as the technical representative of the plugin to the WordPress core. The defining characteristic that allows WordPress to recognize this file as a plugin is the presence of a standardized file header, a specially formatted block of PHP comments located at the very top of the file. This header is parsed by the WordPress core function get_plugin_data(), which is optimized to scan only the initial of the file to identify metadata.

| Header Field | Description and Purpose | Regulatory Status |

| Plugin Name | The primary display name in the administration dashboard. | Mandatory |

| Plugin URI | A unique URL for the plugin’s home page or documentation. | Highly Recommended |

| Description | A concise summary (ideally under 140 characters) of the plugin utility. | Required for Directory |

| Version | A semantic versioning string used for update tracking (e.g., 1.0.0). | Mandatory |

| Author | The name of the developer or organization responsible for the code. | Highly Recommended |

| License | The specific legal framework (usually GPLv2 or later). | Mandatory for Repo |

| Text Domain | A unique identifier for internationalization and translation loading. | Required for i18n |

| Requires at least | The minimum version of WordPress core necessary for operation. | Mandatory for PCP |

| Requires PHP | The minimum version of PHP required (e.g., 7.6 or higher). | Mandatory for PCP |

While only the “Plugin Name” field is strictly required for local recognition, the broader set of headers is essential for professional distribution. For instance, the “Text Domain” must match the plugin folder name to ensure that translation files are correctly associated with the plugin’s output. Furthermore, specifying the “Requires at least” and “Requires PHP” fields provides a safety mechanism that prevents the plugin from activating on environments where it might cause technical instability or fatal errors due to incompatible syntax or missing core functions.

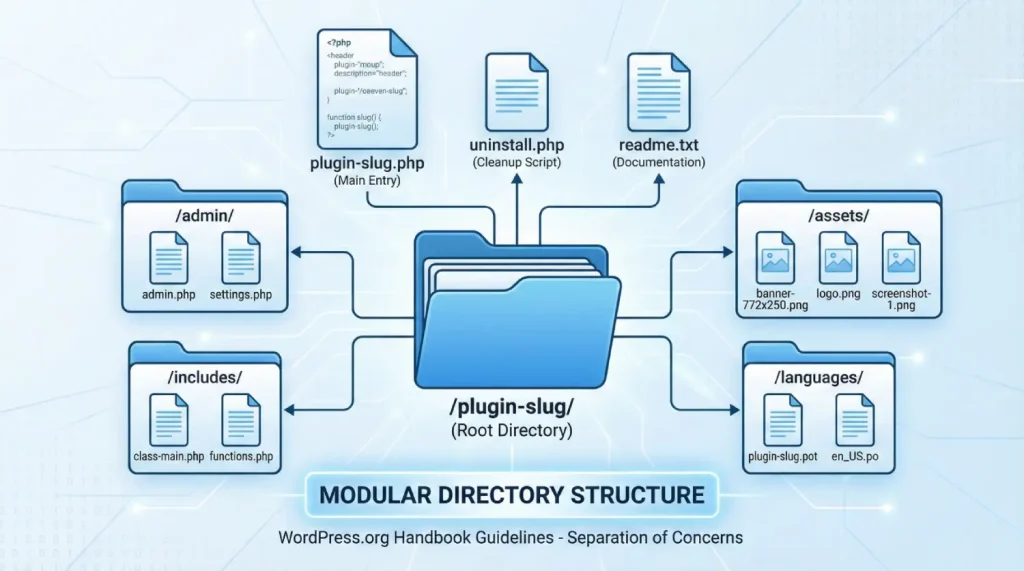

However, much as a basic plugin might technically be a single PHP file put in the /wp-content/plugins/ directory, there is a professional development convention of a modular and organized folder structure. A clear directory structure makes maintenance easier and gives a better readability of the code, as well as compatibility with popular deployment tools. The WordPress.org Handbook proposes a particular layout in order to keep the ecosystem consistent.

A professional plugin directory typically partitions administrative logic, public-facing assets, and core functional logic into discrete subdirectories. This separation of concerns is not merely aesthetic; it prevents the cluttering of the root directory and simplifies the process of enqueuing resources. Standard practice involves creating an assets or public folder for CSS, JavaScript, and images, ensuring that these resources are not scattered through the logic files.

A comprehensive plugin architecture usually follows this template:

This structure allows the developer to use path constants effectively. By utilizing functions like plugin_dir_path( __FILE__ ) and plugin_dir_url( __FILE__ ), the plugin can dynamically determine its location on the server or via a URL, which is critical for sites that use non-standard directory structures or SSL.

One of the most frequent errors of beginners who are starting out is to manually add either <script> or <style> tags in the header or footer of the website. WordPress requires a centralized enqueuing system to handle assets. The process enables WordPress to resolve dependencies, eliminate redundant loading of libraries such as jQuery and optimize the performance of the site by using prudent positioning of scripts.

The orchestration of assets is handled through the wp_enqueue_script() and wp_enqueue_style() functions. These must be executed within specific action hooks depending on the intended context of the resource. For example, scripts intended for the public-facing side of the site should be hooked into wp_enqueue_scripts, while administrative assets require the admin_enqueue_scripts hook.

| Enqueue Component | Function and Importance | Implementation Detail |

| Handle | A unique identifier for the script or style. | Used as a reference by other plugins to manage dependencies. |

| Source | The full URL to the asset file. | Generated using plugin_dir_url() to ensure portability. |

| Dependencies | An array of handles that must be loaded first (e.g., array(‘jquery’)). | WordPress automatically manages the loading order based on this list. |

| Version | A version string for cache busting. | Can be set to the plugin version or null to avoid cache strings. |

| Strategy | The loading method, such as defer or async. | Introduced to improve modern performance metrics and core web vitals. |

The fundamental mechanism that enables WordPress extensibility is its hook-driven architecture. Hooks allow a plugin to “intercept” the execution of WordPress at specific, pre-defined points to either perform a task or modify data. This system is divided into two primary types: Actions and Filters. Understanding hooks is important as a professional developer, as it allows for the implementation of features without altering the core software or other plugins.

While beginners often confuse the two, Actions and Filters serve distinct architectural purposes. An Action is a trigger used to “do something” when a specific event occurs. For example, when WordPress reaches the end of the page rendering, it triggers the wp_footer action, allowing plugins to inject tracking scripts or custom HTML before the closing body tag. Actions do not return data to the core; they merely perform an act and allow execution to continue.

Conversely, a Filter is used to “change something”. Filters intercept data as it is being processed and allow a plugin to modify that data before it is saved to the database or displayed to the user. A callback function for a filter must return the modified data to the hook. A common example is the the_content filter, which allows a plugin to append a signature or copyright notice to the end of every post.

| Hook Category | Goal | Callback Requirement | Contextual Example |

| Action | Execution of a task at a specific moment. | Performs a task (echo, DB update); returns nothing. | wp_footer: Adding a modal or script to the page footer. |

| Filter | Modification of data before use. | Accepts data, modifies it, and must return it. | the_title: Appending “Breaking News:” to specific post titles. |

In a complex ecosystem where multiple plugins may hook into the same event, the order of execution is critical. WordPress uses a priority system, where developers can specify an integer (defaulting to 10) during the registration of a hook. Functions with lower priority numbers are executed earlier. If a plugin needs to ensure its modifications are the final ones applied to a string of content, it might use a high priority number like 99. Furthermore, if a hook passes multiple arguments to a callback function, the developer must explicitly state the number of accepted arguments in the add_action() or add_filter() call to avoid PHP warnings.

Security is the most critical aspect of WordPress plugin development, as vulnerabilities in third-party code account for the vast majority of exploits in the ecosystem. The Plugin Check Plugin (PCP) places heavy emphasis on security validation, and failing these checks is the primary reason for repository rejection. The modern security strategy for WordPress is built on three pillars: sanitizing inputs, validating data integrity, and escaping outputs.

Every piece of data that enters a plugin, whether from a user-submitted form, a URL parameter, or an external API, is considered untrusted. Sanitization is the process of cleaning this data to ensure it is safe for processing or storage. For example, sanitize_text_field() strips HTML tags and excessive whitespace from a string, while sanitize_email() removes characters that are invalid in an email address.

Validation is the secondary check that ensures the sanitized data is of the expected type or within a specific range. Even if the data is sanitized, it may still be logically incorrect. For instance, if a plugin expects a numeric ID but receives the string “dog,” sanitization might result in an empty string or zero. Still, validation would identify that the input is not a valid number.

Escaping is the final defense against Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. It involves securing data at the moment of output to the browser, ensuring that any malicious scripts are rendered as harmless text. Escaping must be context-specific; the function used depends on where the data is being placed in the HTML structure.

| Escaping Function | Contextual Usage | Security Impact |

| esc_html() | For text displayed within standard HTML tags. | Prevents the execution of <script> tags embedded in text. |

| esc_attr() | For data used inside HTML attributes (e.g., value=”…”). | Prevents attackers from breaking out of an attribute to inject new tags. |

| esc_url() | For links, images, and resource paths. | Sanitizes the protocol and removes dangerous characters from URLs. |

| esc_js() | For data outputted inside inline JavaScript blocks. | Escapes quotes and special characters to prevent JS injection. |

| wp_kses_post() | For content that is allowed to contain safe HTML. | Filters out dangerous tags (like <iframes> or <scripts>) while keeping formatting. |

Nonces, or “numbers used once,” are cryptographic tokens used to verify that a request was intentionally made by the authorized user. They are the primary defense against Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). A common PCP error involves processing form data without a nonce, which could allow an attacker to trick an administrator into performing sensitive actions. Developers must generate a nonce using wp_create_nonce() and verify it upon receipt using wp_verify_nonce() before any state-changing logic is executed.

Most of the plugins need permission to access and save data in the WordPress database. Although WordPress offers high-level APIs for either simple settings (Options API) or categorization (Taxonomies), complicated data may need a connection to the global object, which is the $wpdb.

The most significant security risk in database operations is SQL injection. To prevent this, developers must never manually concatenate variables into a SQL string. Instead, they must use the $wpdb->prepare() method, which uses placeholders to safely escape data before the query is executed. The prepare function supports placeholders like %s for strings, %d for integers, and %f for floats.

An architectural requirement for all database-interacting plugins is the respect for the website database prefix. Hard-coding the default wp_ prefix is a significant error, as many sites change this prefix for security or multisite organization. Developers must always retrieve the current prefix using the $wpdb->prefix property to ensure the plugin remains portable across different installations.

Beginners often create custom database tables for data that could be more effectively managed through existing WordPress structures. The decision on where to store data should be based on its intended use and longevity.

| Data Type | Recommended Storage Method | Rationale |

| Persistent settings | wp_options table. | Optimized for small, site-wide configuration values. |

| Temporary/Cached data | Transients API. | Automatically expires; often stored in fast object caches. |

| Complex entities | Custom Post Types (CPT). | Leverages built-in search, status, and metadata functionality. |

| Categorization data | Custom Taxonomies. | Optimized for sorting and filtering multiple entities. |

| Log data | File-based logging or dedicated tables. | Prevents standard tables from bloating with non-entity data. |

For a plugin to be accepted into the official WordPress.org directory, it must adhere to a set of guidelines that prioritize the safety and rights of the user. These guidelines are not merely suggestions; they are the criteria against which every submission is judged during the manual and automated review processes.

One of the requirements is that all the plugins should be compatible with the GNU General Public License (GPL) version 2 or above. This compatibility is applied to all the assets in the directory of the plugins, such as third-party libraries, images and fonts. In addition, developers are forbidden to place in their applications trialware, functionality that is crippled or limited, but only to be opened on payment. Although a plugin may serve as an entry point into a paid service (serviceware), all the code hosted on WordPress.org should be fully accessible and operational.

The directory standards require that code be human-readable. Obfuscation techniques, such as those that mangle variable names or compress code into unreadable strings, are forbidden as they are often used to hide malicious logic. Additionally, plugins must implement measures to prevent direct file access leaks. By adding a check for the ABSPATH constant at the beginning of every PHP file, developers ensure that the script cannot be executed outside of the WordPress environment, which could otherwise expose sensitive paths or logic.

The WordPress.org plugin review process has undergone a significant transformation. New submissions are now required to pass the “Plugin Repo” category of the Plugin Check Plugin (PCP) before they can even enter the manual review queue. This shift was designed to reduce the backlog of reviews by empowering authors to identify and fix common architectural and security errors autonomously.

PCP is a testing tool that performs both static and dynamic checks. Static checks utilize PHP_CodeSniffer with WordPress-specific “sniffs” to analyze the source code for patterns that violate standards, such as missing sanitization or hard-coded database prefixes. Dynamic checks involve the tool actually activating the plugin on a localized server to monitor for PHP warnings, performance impacts, or improper usage of core functions during the execution cycle.

| PCP Category | Critical Focus Areas | Compliance Implication |

| Plugin Repo | Header accuracy, trademark checks, and readme validation. | Mandatory; any “Error” here blocks the submission. |

| Security | Nonce verification, output escaping, and input sanitization. | Essential for approval; flags common vulnerabilities. |

| Performance | Asset enqueuing, resource management, and query efficiency. | Highly recommended; identifies code that slows down sites. |

| Internationalization | Correct function usage, text domain consistency. | Required for plugins intended for a global audience. |

While PCP is a powerful ally for code quality, it is not infallible. Developers frequently encounter “false positives”, instances where the tool flags a legitimate coding pattern as an error. A notable example is the flagging of the _e() function for internationalization; while PCP may demand esc_html_e(), the original code may be perfectly safe in its specific context. In such cases, developers can utilize inline annotations, such as // phpcs:ignore, to tell the scanner to overlook a specific line, provided they have ensured the code is secure through other means.

However, the “Plugin Repo” category is less flexible. Common failures in this category include mismatched version numbers between the plugin header and the readme.txt file, or using “Tested up to” versions that are too old or too new. Fixing these PCP errors is not just about passing a test; it is about ensuring that the plugin provides accurate metadata to the WordPress update system and the user-facing directory.

To successfully navigate the PCP requirements, developers should integrate the tool directly into their local development environment. PCP can be run through the WordPress Admin interface under Tools > Plugin Check or via the command line with WP-CLI.

esc_html(), esc_attr(), or wp_kses_post() accordingly.--require argument with WP-CLI to perform runtime checks, ensuring that the plugin does not generate headers-already-sent warnings or PHP notices upon activation.The responsibility of a plugin developer extends beyond the initial publication. Maintenance involves responding to security disclosures, ensuring compatibility with new WordPress versions, and providing a clean uninstallation process.

A well-architected plugin must respect the user site environment by removing all its data upon deletion. Beginners often mistakenly use the deactivation hook for this purpose, but this results in data loss if the user only intended to temporarily disable the plugin. The correct approach is to create an uninstall.php file in the plugin root.

This “magic file” is executed only when the user chooses to delete the plugin from the admin interface. The script must begin with a security check for the WP_UNINSTALL_PLUGIN constant to prevent unauthorized execution. Inside the script, the developer should systematically remove all options, transients, and custom database tables that the plugin created.

| Cleanup Target | Recommended Action | Risk of Failure |

| Settings and Options | Use delete_option() for all registered keys. | Causes the wp_options table to bloat over time. |

| Custom Tables | Use $wpdb->query( “DROP TABLE…” ). | Leaves orphaned database structures that complicate migrations. |

| Created Files | Use PHP unlink() to remove files in wp-content. | Leaves “junk” data on the server, increasing backup sizes. |

| Active Shortcodes | No direct cleanup; usually handled via __return_false in themes. | Leaves broken shortcode tags (e.g., [my_plugin]) in post content. |

Security is an elusive concept within the contemporary ecosystem. Almost 8,000 WordPress plugins were found to have vulnerabilities. Professional developers should also keep track of security disclosure platforms such as Wordfence or Patchstack, and also be ready to issue patches within 7-14 days of a private disclosure. Any non-action taken in regard to these disclosures in most cases will cause the WordPress.org team to temporarily shut the plugin to new installations to safeguard the user base.

The implementation of mandatory 2FA and automated PCP scans for updates represents a proactive shift toward a “secure-by-design” ecosystem. By using PCP not just for initial submission but as a recurring part of the update cycle, developers can identify deprecated functions or new performance bottlenecks before they reach the user.

A WordPress plugin is a complicated piece of execution of the PHP code, the integration of core APIs, and regulatory compliance. To the novice, the way forward is characterized by three main commitments: the isolation provided by unique prefixing of the architecture, the importance given to the “Sanitize, Validate, Escape” model of security, and the strict application of the Plugin Check Plugin (PCP) as a quality gate.

The barrier to entry has also increased naturally as the WordPress ecosystem keeps expanding in order to safeguard the millions of websites that use third-party code. The transition to the automated compliance system and AI-improved reviews as a part of the PCP framework is the required step to provide the long-term stability and security of the web. The aspiring plugin writer can also make a difference on a worldwide platform, coming up with operational software that is also robust, portable, and secure, without considering these requirements as obstacles but rather as a guideline towards becoming a professional. The outcome is the development of a plugin that will cooperate effectively in the heterogeneous and unstable context of the global WordPress community, so that the extension process of the core will be a safe and fruitful activity for all the interested parties.

Hassan Tahir wrote this article, drawing on his experience to clarify WordPress concepts and enhance developer understanding. Through his work, he aims to help both beginners and professionals refine their skills and tackle WordPress projects with greater confidence.