- Lifetime Solutions

VPS SSD:

Lifetime Hosting:

- VPS Locations

- Managed Services

- Support

- WP Plugins

- Concept

The interface between the server-side scripting language and the underlying host infrastructure is the key element of the architecture of modern web development, on which all dynamic applications are based. To the developers who are using PHP (Hypertext Preprocessor), this interface is not a fixed structure but a dynamic, tunable, run-time environment that determines not only how much memory is available, how much time can be used, but also how secure the system is and what extensions are available. The most important way of introspecting this complex internal state is the phpinfo() function. Although often dismissed as a simple version checker by novice practitioners, the phpinfo diagnostic page is a detailed dump of the internal registry of the PHP runtime and reveals thousands of directives, environment variables, compilation flags, and module statuses that define the ability of the server to run code.

The report is a comprehensive, professional-level assessment of the phpinfo tool in the framework of a localhost development environment. It is aimed to steer the reader through the entry-level notion of how to build the page, to the second level of knowledge to properly diagnose unknown configuration conflicts, to optimize performance of content management systems (CMS) such as WordPress or Drupal, and to protect the environment against information disclosure vulnerabilities. We will go through the conceptual structure of the Server API (SAPI), the practicality of configuration on the various local stacks (XAMPP, WAMP, MAMP, Docker) and the hygiene of the security that is necessary to work with this sensitive information.

In computer science, the term introspection denotes the capability of a program to look at itself and its on-the-fly state. The nature of PHP, as an interpreted language, is that it depends on a runtime environment, which is initialized at each request (in the case of CGI) and is kept specific to the server and highly visible through introspection tools. PHP is a transparent layer, unlike compiled languages such as C++ or Rust, where the configuration of the runtime environment has been baked into the binary and is often obscured after compilation.

The phpinfo() function is the standard-bearer for this capability. When a developer executes this function, they are not merely printing text; they are querying the core engine for a status report on:

The term “localhost” technically refers to the loopback network interface, universally mapped to the IP address 127.0.0.1 (IPv4) or::1 (IPv6). Developing locally allows for rapid iteration cycles, the “code-save-refresh” loop, without the latency of network transmission or the risk of exposing unfinished, insecure code to the public internet. However, local environments are notoriously fragmented. A script that functions flawlessly on a Windows machine running WAMP may fail catastrophically on a Linux Docker container due to subtle differences in case sensitivity, directory separators, or enabled extensions.

The phpinfo page is serving as the ground truth in this fragmented landscape. It resolves ambiguity. When a developer makes a mistake, like in the example of the error of file upload exceeded, the particular limit is not in the code, but in the server setup. In instances where a date function gives the wrong time, this error is in the date. timezone configuration of the runtime, and may not always be the script logic. Thus, the phpinfo page generation and correct interpretation are the conditions for further development of PHP and server management.

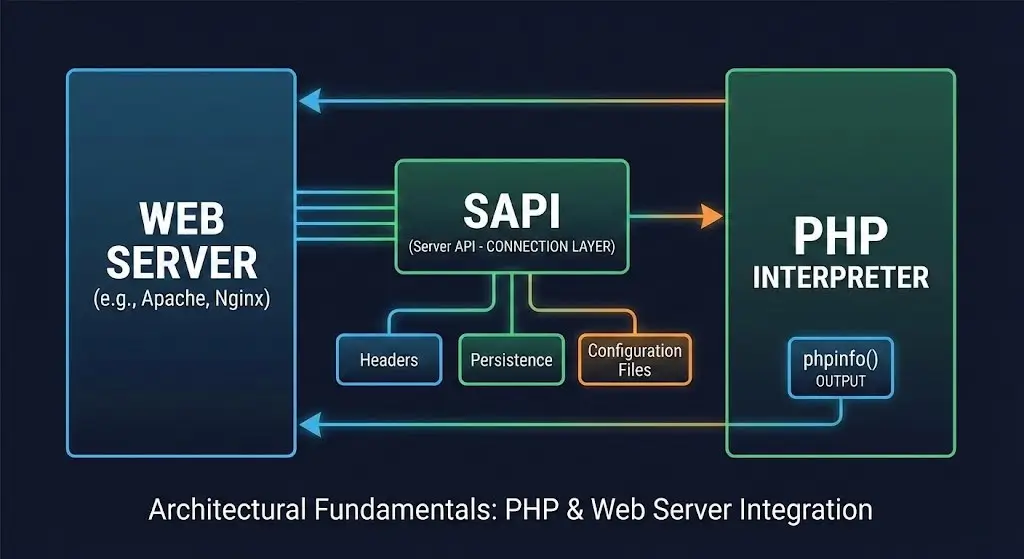

To interpret the output of phpinfo() correctly, one must understand the mechanism by which it is generated. The output is not static; it changes fundamentally depending on how PHP is connected to the web server. This connection is defined by the Server API (SAPI).

The SAPI is the interface PHP uses to communicate with the host environment. The topmost section of a phpinfo page explicitly states the “Server API,” and this single data point dictates the behavior of many subsequent directives, including how headers are sent, how persistence works, and which configuration files are loaded.

Comparison of Common PHP Server APIs (SAPI)

| SAPI Type | Technical Description | Ecosystem Prevalence | Implications for phpinfo() Analysis |

| Apache 2.0 Handler (mod_php) | PHP is loaded as a shared library (.so or .dll) directly inside the Apache process memory space. | XAMPP (Default), WAMP, Legacy Linux setups. | Shows Apache 2.0 Handler. PHP runs with the same user permissions as Apache. Configuration changes usually require a full Apache restart. .htaccess overrides are natively supported. |

| CGI / FastCGI | PHP runs as a separate process from the web server. The server forwards requests to PHP via a socket or TCP port. | IIS (Windows), Shared Hosting, Nginx (occasionally). | Shows CGI/FastCGI. Environment variables are passed differently. php.ini is re-read more frequently in standard CGI, whereas FastCGI processes are persistent to reduce overhead. |

| FPM (FastCGI Process Manager) | A highly specialized version of FastCGI with advanced process management, adaptive spawning, and logging. | Nginx (LEMP stacks), High-performance Apache, Docker containers. | Shows FPM/FastCGI. Highly configurable pool settings. The phpinfo output will contain a dedicated FPM section detailing the pool name and process manager status. |

| CLI (Command Line Interface) | PHP runs from the terminal, independent of a web server. | Scripts, Cron Jobs, REPL, Package Managers (Composer). | Shows Command Line Interface. Crucial Distinction: CLI often uses a different php.ini file than the web server. Directives like max_execution_time default to 0 (infinite) in CLI but 30 in Web SAPI. |

| Built-in Web Server | PHP’s internal development server. | Quick prototyping (php -S localhost:8000). | Shows Built-in Web Server. Limited concurrency, single-threaded. Not suitable for production simulation, but useful for quick phpinfo checks. |

Insight: A pervasive source of confusion for beginners is editing the php.ini file and observing no change in the phpinfo() output. This phenomenon frequently occurs because the developer has edited the CLI configuration file (e.g., /etc/php/8.1/cli/php.ini) while the web server is actually reading the FPM configuration file (e.g., /etc/php/8.1/fpm/php.ini). The phpinfo() page is the definitive authority for identifying which configuration file is currently active, overruling any assumptions the developer might have.

Understanding the lifecycle helps in troubleshooting why a page might fail to load. When a user requests http://localhost/phpinfo.php:

If this chain is broken, for example, if the MIME type application/x-httpd-php is missing, the server will default to treating the file as plain text or a binary download, causing the browser to download the PHP source code rather than displaying the result.

Before one can create a phpinfo page, one must know where to create it. The “Document Root” varies significantly across the diverse ecosystem of localhost tools.

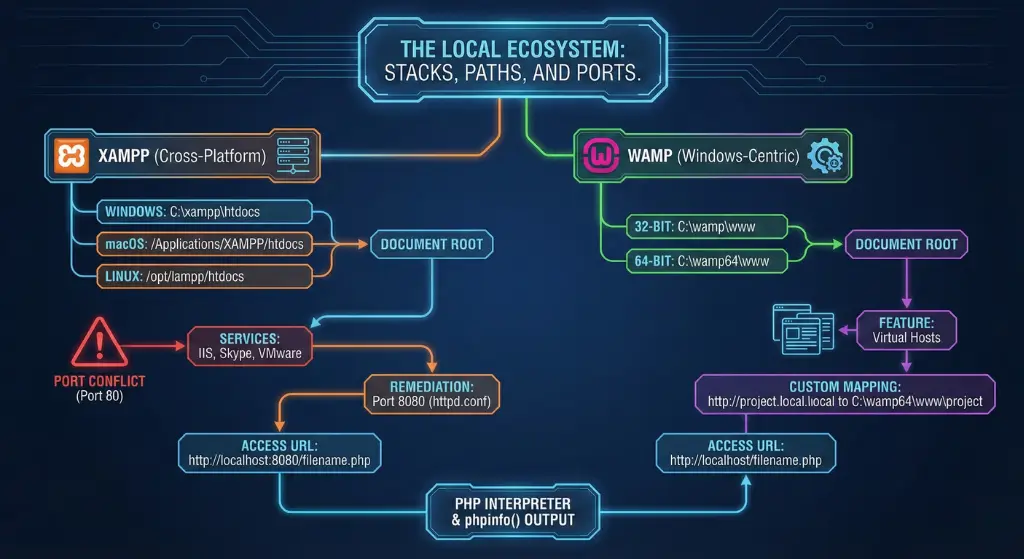

XAMPP is arguably the most ubiquitous local development stack due to its ease of installation on Windows, macOS, and Linux.

Insight – Port Conflicts: A distinct characteristic of XAMPP users on Windows is the frequent conflict with port 80. Services like World Wide Web Publishing Service (IIS), Skype, or VMware often claim port 80. If XAMPP Apache fails to start, the standard remediation is to modify httpd.conf to listen on port 8080. Consequently, the access URL shifts to http://localhost:8080/filename.php. The phpinfo page will reflect this in the $_SERVER variable.

WAMP is a Windows-centric stack that offers a tray-icon interface for switching PHP versions on the fly.

Insight – Virtual Hosts: WAMP encourages the use of Virtual Hosts. While the www folder is the default, advanced WAMP setups might map http://project.local to C:\wamp64\www\project. In this case, creating a phpinfo page in the project root allows for project-specific introspection, which is vital if different projects are configured to use different PHP versions.

Originally designed for macOS, MAMP is now available on Windows. It isolates itself from the system’s pre-installed Apache/PHP to prevent conflicts.

Docker represents a paradigm shift where the “localhost” is actually a virtualized container running a stripped-down Linux OS (usually Alpine or Debian).

The creation of the phpinfo page is a trivial coding task, but it requires adherence to strict file formats and permissions to function correctly.

The code required is universally consistent across all platforms. A standard file, typically named phpinfo.php or info.php, contains the following lines:

<?php

phpinfo();

?>Critical Warning on PHP Tags: A frequent point of failure for beginners is the use of “Short Open Tags” (<? phpinfo();?>). By default, many modern production-grade php.ini configurations have short_open_tag = Off to avoid conflicts with XML declarations (which also start with <?). If short tags are disabled, the server will treat the code as plain text and display the code itself rather than executing it. It is an industry best practice to always use the full <?php opening tag to ensure portability.17

The file must be saved as plain text.

Unlike Windows, Linux enforces strict file ownership. A user might create a file in their home directory and move it to /var/www/html using sudo, resulting in a file owned by the root user. If the web server (typically running as user www-data on Ubuntu/Debian or apache on CentOS) does not have read permissions for this file, it will return a 403 Forbidden error.

Remediation:

sudo chown www-data:www-data /var/www/html/info.php

sudo chmod 644 /var/www/html/info.phpThe chmod 644 command grants the owner read/write access and everyone else (including the web server if not the owner) read-only access.

Although the normal usage is not argumentative, the phpinfo() function has fine configurable controls with the ability to acquire customized output. This comes in handy, especially during the debugging of certain subsystems without creating a huge HTML payload.

The function accepts a single optional parameter: int $flags. This parameter is a bitmask, meaning multiple constants can be combined using the bitwise OR operator (|) to aggregate specific sections of data.

phpinfo() Constants and Output Sections

| Constant | Value | Description | Utility Case |

| INFO_GENERAL | 1 | The “header” information: System line, Build Date, Web Server API, and Config File Path. | Quick verification of Architecture (x86 vs x64) and Thread Safety (TS/NTS).1 |

| INFO_CREDITS | 2 | Lists PHP developers and contributors. | Rarely used for technical diagnostics. |

| INFO_CONFIGURATION | 4 | Vital: Displays current Local and Master values for all PHP directives. | The primary section for tuning memory_limit or upload_max_filesize.2 |

| INFO_MODULES | 8 | Vital: Lists all loaded extensions and their individual settings. | verifying if mysqli or gd libraries are loaded and checking their versions.2 |

| INFO_ENVIRONMENT | 16 | Shows environment variable information ($_ENV). | Critical for debugging Docker containers or 12-factor apps where config is injected via ENV.1 |

| INFO_VARIABLES | 32 | Shows predefined variables from EGPCS (Environment, GET, POST, Cookie, Server). | Security auditing: checking cookie values or session tokens.1 |

| INFO_LICENSE | 64 | The PHP License text. | Legal compliance checks. |

| INFO_ALL | -1 | Displays all of the above. | The default behavior when no parameter is passed. |

Example of Selective Output:

If a developer needs to verify loaded modules and configuration but wants to suppress the long credit list and license text (to keep the page short):

<?php

// Show only Modules and Configuration

phpinfo(INFO_MODULES | INFO_CONFIGURATION);

?>phpinfo() is designed to output directly to the browser’s output stream. It returns a Boolean TRUE on success, not the data itself. To capture the data into a variable for parsing (e.g., to create a custom dashboard that shows the PHP version in the admin panel), one must use Output Buffering.

ob_start(); // Start recording output

phpinfo(); // Execute function (output goes to buffer, not screen)

$server_data = ob_get_contents(); // Save buffer to variable

ob_end_clean(); // Stop recording and discard buffer

// Now $server_data contains the HTML string, which can be parsed

if (strpos($server_data, 'xdebug')!== false) {

echo "Xdebug is installed!";

}This technique is widely used by CMS plugins (like WordPress Site Health) to report on server status without displaying the raw, unstyled phpinfo table.

To the untrained eye, the phpinfo page is a wall of noise. To the expert, it is a map of the server’s capabilities. We will deconstruct the page section by section to understand the implications of the data presented.

The first block contains the fundamental identity of the PHP process.

This is often the most critical section for troubleshooting configuration persistence issues.

The “Core” section details the runtime behavior. The table presents two columns for each directive:

The Debugging Utility: If a developer sets memory_limit to 512M in php.ini but the application crashes with an Out of Memory error, looking at phpinfo might reveal a Local Value of 128M and a Master Value of 512M. This discrepancy proves that the global config is correct, but something “downstream”, likely an .htaccess file or an ini_set(‘memory_limit’, ‘128M’) line in the CMS core, is overriding it. This isolates the problem away from the server config and toward the application code.

Modern web applications require specific extensions to function. phpinfo verifies their presence and version.

The EGPCS (Environment, GET, POST, Cookie, Server) sections display the data PHP received from the server and the browser.

The primary utility of the phpinfo page is to guide configuration changes. A “vanilla” PHP installation usually comes with conservative defaults (e.g., 2MB upload limit) that are insufficient for modern application development.

The first step in any tuning exercise is finding the correct file to edit. As established in Section 6.2, one must consult the “Loaded Configuration File” row.

The following directives are the most frequently adjusted in local environments.

Controls the maximum amount of RAM a single PHP script execution is allowed to consume.

These two directives act as a gatekeeper for file uploads and must be configured in tandem.

The time limit, in seconds, a script is allowed to run before the parser terminates it.

PHP reads the php.ini file only once upon startup (in Module/FPM modes). Changes made to the file are not applied dynamically.

While phpinfo() is an invaluable diagnostic instrument, it represents a significant Information Disclosure vulnerability (CWE-200) if exposed to unauthorized actors.

Why is a simple status page dangerous?

Even in a localhost environment, security is paramount. If the development machine is connected to a public Wi-Fi network, or if a router has UPnP (Universal Plug and Play) enabled, “local” services can sometimes be reached from the outside.

The most robust defense is to configure the web server to strictly allow access only from the loopback address (127.0.0.1 and ::1). This blocks any request originating from another machine on the LAN or the internet.

Apache Configuration (.htaccess):

Create a .htaccess file in the same directory as info.php:

<Files "info.php">

<RequireAny>

Require ip 127.0.0.1

Require ip ::1

</RequireAny>

</Files>For older Apache 2.2 setups, the syntax is:

Order Deny,Allow

Deny from all

Allow from 127.0.0.1

Allow from ::1Precedence: Note the order. In Apache 2.2, Order Deny, Allow means “Deny everything by default, then process Allows.” If you reverse it, you might accidentally leave it open.38

Nginx Configuration:

In the server block config:

location = /info.php {

allow 127.0.0.1;

allow ::1;

deny all;

include snippets/fastcgi-php.conf;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php/php8.1-fpm.sock;

}This restricts access at the network stack level, returning a 403 Forbidden to any other IP.

If the local server must be accessed by other devices on the LAN (e.g., testing on a mobile phone), the IP restriction is too strict. In this case, implement Basic Authentication.

PHP Wrapper Solution:

Instead of raw phpinfo(), use a wrapper script that requires a hardcoded password:

<?php

$username = 'admin';

$password = 'secure_password';

if (!isset($_SERVER) ||!isset($_SERVER) ||

$_SERVER!= $username |

| $_SERVER!= $password) {

header('HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized');

header('WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="Secure Area"');

exit('Unauthorized Access');

}

// Only runs if auth succeeds

phpinfo();

?>This forces a browser login prompt before executing the info function.

The safest phpinfo page is the one that no longer exists. A common best practice for one-time diagnostics is to create a “suicide script” that deletes itself immediately after execution.

<?php

phpinfo();

// Delete this file from the filesystem after execution

unlink(__FILE__);

?>When the developer visits this page, they see the info once. If they refresh the page, they get a 404 Not Found error because the file has deleted. This prevents the accidental “leave-behind” of sensitive diagnostic files.

The phpinfo() page is the Rosetta Stone of the PHP environment. It translates the silent, invisible configurations of the web server and operating system into readable, actionable data. For the beginner, it acts as a confirmation of life, proof that the stack is installed and operational. For the intermediate developer, it is the manual for the environment, dictating which libraries are available and what limits are enforced. For the expert systems architect, it provides the forensic data necessary to diagnose SAPI conflicts, optimize bytecode caching, and audit security postures.

However, the very utility of phpinfo() lies in its total transparency, which makes it a liability. Mastering this tool requires a dual discipline: the technical acumen to interpret its thousands of data points to build robust applications, and the operational rigor to restrict its access, ensuring that the server’s internal anatomy remains private. By understanding the architectural context of SAPI, the hierarchy of configuration loading, and the mechanisms of web server access control, a developer transforms phpinfo() from a simple debugging trick into a precise, professional diagnostic instrument.

Hassan Tahir wrote this article, drawing on his experience to clarify WordPress concepts and enhance developer understanding. Through his work, he aims to help both beginners and professionals refine their skills and tackle WordPress projects with greater confidence.