- Lifetime Solutions

VPS SSD:

Lifetime Hosting:

- VPS Locations

- Managed Services

- Support

- WP Plugins

- Concept

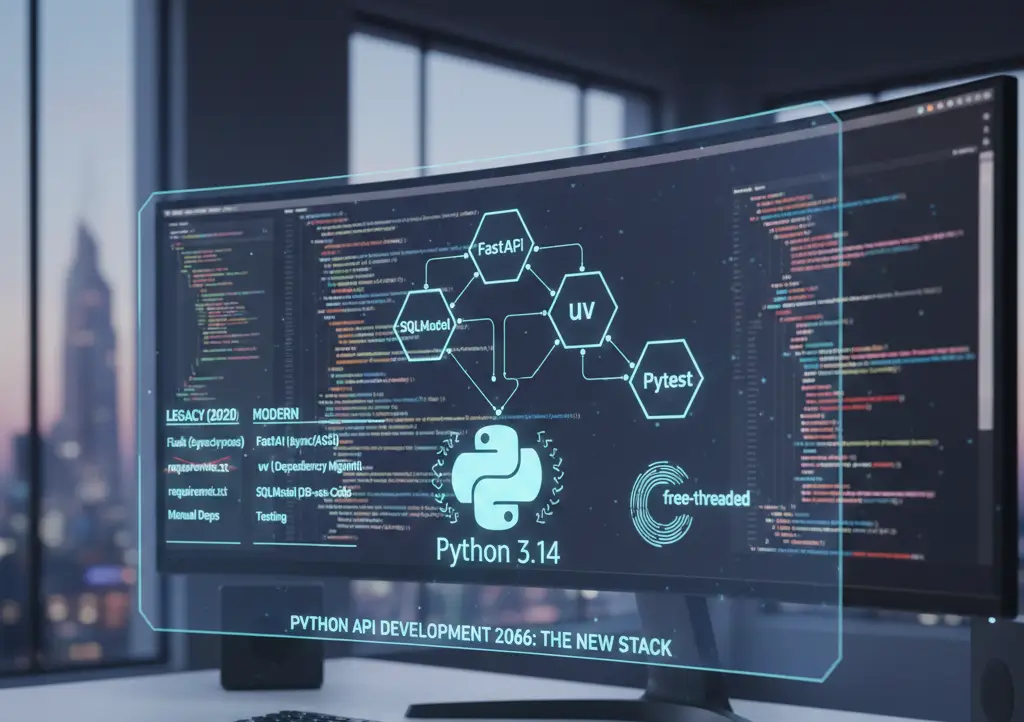

In mid-2020, Python API development went through a paradigm shift in its structure. We have transitioned out of the monolithic, synchronous, and manual dependency management into a high-performance asynchronous execution, strict type safety, and single-tooling age. By 2026, when Python 3.14 has reached free-threaded, FastAPI framework has become the standard, and Rust-powered development tools such as uv have reached maturity, the Python development experience has become as fast as compiled languages in throughput but still maintains the legendary Python developer ergonomics.

The report can be regarded as a comprehensive, introductory document for developers joining the industry in 2026. It breaks down the conceptual foundation of web APIs, examines the existing framework ecosystem, and offers an intensive, structured practicum on how to design systems of production quality. Going beyond legacy, i.e., use of requirement.txt or synchronous Flask routes, and adopting the current stack of FastAPI, SQLModel, uv and Pytest, developers are enabled to build not just performant but maintainable and scalable APIs. We are going to discuss how modern Python takes advantage of the built-in ASGI standard to serve thousands of parallel connections, how dependency injection eases architecture, and how the database-as-code paradigm has brought data validation and persistence together.

An API engineer should have an intuition about the web protocols and architecture styles that dictate the web before they even write a line of code. Application Programming Interface (API) is not a technical contract; it is an agreement between software units. By 2026, new protocols such as HTTP/3 and new paradigms such as gRPC will be available, but the RESTful architecture over HTTP will form the basis of general-purpose web development.

The application-layer protocol, which drives the web, is the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). Modern API frameworks abstract this away, but a subtly aware grasp of the meaning of HTTP is what makes the difference between a junior developer and a top architect.

At its core, a web API operates on a request-response cycle. A client (browser, mobile app, or another server) initiates a Request, which consists of a method (verb), a URI (resource identifier), headers (metadata), and an optional body (payload). The server processes this and returns a Response, containing a status code, headers, and a body.

The ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface) specification manages this cycle in the Python ecosystem of 2026. In contrast to the older standard of WSGI, which was a blocking (synchronous) standard, ASGI permits the server to process the request-response cycle in a non-blocking fashion, allowing a high level of concurrency. Upon receiving a request, the ASGI server (such as Uvicorn) decomposes the raw TCP stream into a Python dictionary of the form of the ASIO of the request, which other frameworks, such as FastAPI thenconsumes.

A critical concept in API design is the distinction between safe and idempotent methods.

Understanding these properties is essential when designing retry logic in distributed systems, a common requirement in modern microservices architectures.

While this report focuses on REST (Representational State Transfer) as it is the primary paradigm for FastAPI and SQLModel, it is vital to situate it within the broader context.

In 2026, the dominance of FastAPI allows for a hybrid approach. While primarily RESTful, FastAPI’s support for Pydantic models means it can easily be adapted to serve GraphQL or utilize high-performance serialization that rivals gRPC in throughput for many use cases.

The Python language itself has evolved significantly. The version 3.14 release cycle has introduced features that fundamentally alter the performance characteristics of Python APIs. To build modern APIs, one cannot rely on the mental models of Python 3.8 or 3.9.

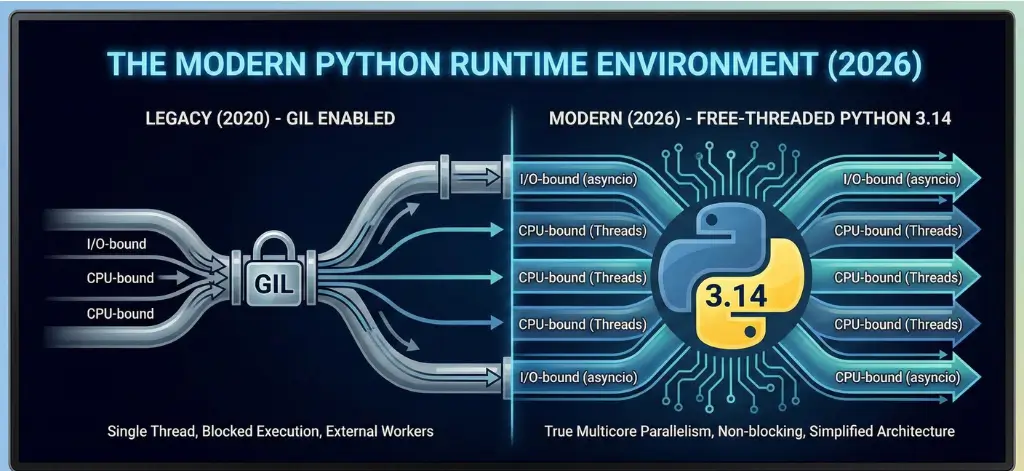

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) was historically the greatest limiter of Python performance. It ensured that only one thread executed Python bytecode at a time, effectively preventing CPU-bound parallelism within a single process.

With the official support for free-threaded Python in 3.14 (PEP 779), the GIL is optional. For API development, this is revolutionary. In previous years, if an API endpoint needed to perform a heavy calculation (e.g., image resizing or complex cryptography), it would block the event loop, causing all other incoming requests to hang. Developers were forced to offload these tasks to external job queues like Celery/Redis.

In 2026, with free-threaded Python, API workers can utilize true multicore parallelism. A single FastAPI process can handle I/O-bound requests (via asyncio) and CPU-bound tasks (via threads) simultaneously without one blocking the other. This simplifies architecture for small-to-medium applications by reducing the need for complex distributed worker setups.

Beyond the GIL, Python 3.14 includes several optimizations that directly benefit web frameworks:

While introduced earlier, asyncio is now the default mode of operation for web development. The async and await keywords allow Python to handle “cooperative multitasking.”

When an API handler executes await session. exec(query), the function pauses. The underlying event loop (often provided by uvloop, a high-performance C implementation used by Uvicorn) immediately switches to processing another incoming request. Once the database returns data, the function resumes. It enables one Python process to support thousands of connections (not one or two) at once with minimal resource overhead, an ability that used to be the preserve of Node.js or Go.

Perhaps the most visceral change for a developer in 2026 is the tooling. The fragmented ecosystem of pip, virtualenv, poetry, pipenv, and pyenv has been largely consolidated into a single, high-performance tool: uv.

uv, developed by Astral, is written in Rust. This architectural choice results in performance that is 10 to 100 times faster than the legacy pip toolchain. In a beginner’s journey, this speed removes friction; installing a massive data science stack takes seconds rather than minutes.

However, uv is not just an installer; it is a lifecycle manager. It replaces the following tools:

The shift from the legacy workflow to the uv workflow represents a move from imperative to declarative management.

Evolution of Python Project Management

| Feature | Legacy Workflow (2020-2023) | Modern Workflow (2026 – uv) | Architectural Impact |

| Project Init | Manual directory creation; touch requirements.txt | uv init project_name | Enforces standard structure from moment zero.3 |

| Environment | python -m venv venv | Automatic on dependency add | Eliminates “forgot to activate venv” errors.16 |

| Dependency: Add | pip install X, then pip freeze > requirements.txt | . uv add X | Updates metadata and lockfile atomically.15 |

| Resolution | Slow, prone to backtracking errors | Near-instant, strictly correct | Faster CI/CD pipelines and developer loops.12 |

| Execution | source venv/bin/activate && python main.py | uv run main.py | Ensures execution always happens in the correct context.3 |

For the remainder of this report, all practical examples will utilize the uv workflow, as it is the current industry best practice for maintainability and speed.

Choosing a framework is an architectural bet on the future. In 2026, the Python web framework market has matured and consolidated. While niche frameworks exist, three dominate the conversation: Django, Flask, and FastAPI.

Django remains the choice for monolithic applications where development speed (time-to-market) for standard features (Auth, Admin, ORM) is prioritized over raw request throughput or architectural flexibility.

Flask defined the microframework era. It gives the developer control over every component.

FastAPI has effectively captured the mindshare of the Python community for API development.

Verdict: For a beginner in 2026, FastAPI provides the steepest learning curve for concepts (Async, Types) but the smoothest road to production. It enforces best practices that prevent bugs, making it the superior choice for this report.

In the past, Python developers faced a violation of the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle. They defined a database model in SQLAlchemy (for the database layer) and a nearly identical schema in Marshmallow or Pydantic (for the API layer).

SQLModel, created by Sebastián Ramírez (the author of FastAPI), solves this. It is a library that is simultaneously SQLAlchemy (an ORM) and Pydantic (a data validation library).

With SQLModel, a single class definition serves two purposes:

However, a naive implementation uses one model for everything. Best practice dictates utilizing inheritance to create specialized versions of the model for different contexts (Create, Read, Update).

The Model Inheritance Pattern

| Model Class | Inherits From | Purpose | Example Fields |

| HeroBase | SQLModel | Shared fields for all contexts. | name, secret_name |

| Hero | HeroBase | The Database Table definition. | Adds id (Primary Key), table=True |

| HeroCreate | HeroBase | Validation for POST requests. | Inherits all, strictly validates inputs. |

| HeroPublic | HeroBase | The API Response schema. | Adds id. Filters sensitive data. |

| HeroUpdate | SQLModel | Validation for PATCH requests. | All fields are Optional (nullable). |

This pattern prevents security issues (like Mass Assignment vulnerabilities where a user injects an is_admin field) and ensures API consumers only see what they are supposed to see.

We will now transition from theory to practice. We will engineer a robust “Hero Management API”. This example is chosen because it demonstrates all CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations, database interactions, and proper architectural layering.

We begin by establishing the project environment using uv. This sets the stage for a reproducible development environment.

Initialize Structure

Bash

uv init hero-api

cd hero-apiThis command creates pyproject.toml and a .python-version file, locking the project to the active Python version.

Install Core Dependencies

We require FastAPI for the web layer and SQLModel for the data layer. The standard extra for FastAPI installs uvicorn (the server), httpx (for testing), and email-validator.

Bash

uv add fastapi --extra standard

uv add sqlmodelThe console will confirm the resolution and installation, updating uv.lock instantly.

Architectural Layout

We will adopt a modular structure, avoiding the anti-pattern of putting all code in a single main.py file.

hero-api/

├── app/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── main.py # Application entry point & configuration

│ ├── models.py # SQLModel definitions

│ ├── database.py # Database engine & dependency injection

│ └── routers/ # (Optional) Route splitting for larger apps

├── tests/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── conftest.py # Test fixtures

│ └── test_main.py # Integration tests

├── pyproject.toml

└── uv.lockThis separation of concerns is critical for maintainability.

In app/models.py, we implement the inheritance pattern discussed in Chapter 5. This code defines the shape of our data.

Python

from typing import Optional

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel

# Base class: Fields shared by most models

class HeroBase(SQLModel):

name: str = Field(index=True) # Indexed for faster search

secret_name: str

age: Optional[int] = Field(default=None, index=True)

# Database Table: Adds table configuration and ID

class Hero(HeroBase, table=True):

id: Optional[int] = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

# API Request Model (Creation): Inherits fields, no extra logic needed

class HeroCreate(HeroBase):

pass

# API Response Model: Guarantees 'id' is present

class HeroPublic(HeroBase):

id: int

# API Request Model (Update): All fields optional for PATCH

class HeroUpdate(SQLModel):

name: Optional[str] = None

secret_name: Optional[str] = None

age: Optional[int] = NoneInsight: Notice how HeroUpdate does not inherit from HeroBase. This is intentional. In HeroBase, a name is required (str). In an update (PATCH), the name might not be sent. Redefining it as Optional[str] = None allows partial updates.

In app/database.py, we manage the connection to SQLite. While SQLite is a file-based database perfect for development and testing, SQLModel (via SQLAlchemy) allows us to switch to PostgreSQL in production by changing only the connection string.

Python

from typing import Annotated, Generator

from sqlmodel import SQLModel, Session, create_engine

from fastapi import Depends

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

# check_same_thread=False is required for SQLite when using async frameworks

connect_args = {"check_same_thread": False}

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, connect_args=connect_args)

def create_db_and_tables():

"""Idempotent creation of tables based on models."""

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

def get_session() -> Generator:

"""Dependency that yields a database session per request."""

with Session(engine) as session:

yield session

# Annotated Dependency for cleaner type hints in path operations

SessionDep = AnnotatedThe get_session function uses the yield keyword, making it a context manager.

This pattern ensures that connections are never leaked, even if the application logic crashes. Using Annotated allows the editor to treat SessionDep as a simple Session object, enabling full autocompletion support.

In app/main.py, we tie everything together. We will implement the endpoints using modern FastAPI practices.

Python

from contextlib import asynccontextmanager

from typing import Annotated, List

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException, Query

from sqlmodel import select

from app.models import Hero, HeroCreate, HeroPublic, HeroUpdate

from app.database import create_db_and_tables, SessionDep

# Lifespan Context Manager: The modern way to handle startup/shutdown

@asynccontextmanager

async def lifespan(app: FastAPI):

create_db_and_tables()

yield

app = FastAPI(lifespan=lifespan)

# CREATE

@app.post("/heroes/", response_model=HeroPublic)

def create_hero(hero: HeroCreate, session: SessionDep):

# Convert Pydantic model to SQLModel (DB) instance

db_hero = Hero.model_validate(hero)

session.add(db_hero)

session.commit()

session.refresh(db_hero) # Refresh to get the generated ID

return db_hero

# READ (List with Pagination)

@app.get("/heroes/", response_model=List[HeroPublic])

def read_heroes(

session: SessionDep,

offset: int = 0,

limit: Annotated[int, Query(le=100)] = 100,

):

heroes = session.exec(select(Hero).offset(offset).limit(limit)).all()

return heroes

# READ (Single Item)

@app.get("/heroes/{hero_id}", response_model=HeroPublic)

def read_hero(hero_id: int, session: SessionDep):

hero = session.get(Hero, hero_id)

if not hero:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Hero not found")

return hero

# UPDATE (Partial)

@app.patch("/heroes/{hero_id}", response_model=HeroPublic)

def update_hero(hero_id: int, hero: HeroUpdate, session: SessionDep):

db_hero = session.get(Hero, hero_id)

if not db_hero:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Hero not found")

# Generate dict of updates, excluding fields not sent by client

hero_data = hero.model_dump(exclude_unset=True)

# Apply updates to the DB object

db_hero.sqlmodel_update(hero_data)

session.add(db_hero)

session.commit()

session.refresh(db_hero)

return db_hero

# DELETE

@app.delete("/heroes/{hero_id}")

def delete_hero(hero_id: int, session: SessionDep):

hero = session.get(Hero, hero_id)

if not hero:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Hero not found")

session.delete(hero)

session.commit()

return {"ok": True}With the code in place, we launch the development server using uv:

Bash

uv run fastapi dev app/main.pyThis command does several things:

A rigorous testing strategy is what differentiates professional engineering from hobbyist coding. In the Python ecosystem of 2026, Pytest is the undisputed standard. It offers a concise syntax and a powerful fixture system that simplifies dependency injection during tests.

For APIs, we focus heavily on Integration Tests. These tests simulate real HTTP requests against the application endpoints, verifying that the router, validation, controller logic, and database interaction all work together correctly.

We must ensure that tests do not run against the development database (database.db). Doing so would corrupt local data and make tests flaky. Instead, we use an in-memory SQLite database.

Setup Dependencies:

Bash

uv add --dev pytest httpxTest Configuration (tests/conftest.py):

This file contains “fixtures” setup functions that Pytest automatically creates and injects into test functions.

Python

import pytest

from fastapi.testclient import TestClient

from sqlmodel import Session, SQLModel, create_engine

from sqlmodel.pool import StaticPool

from app.main import app

from app.database import get_session

@pytest.fixture(name="session")

def session_fixture():

"""

Creates an isolated in-memory database for each test.

StaticPool is required for in-memory SQLite with FastAPI's concurrency.

"""

engine = create_engine(

"sqlite://",

connect_args={"check_same_thread": False},

poolclass=StaticPool

)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

with Session(engine) as session:

yield session

@pytest.fixture(name="client")

def client_fixture(session: Session):

"""

Creates a TestClient that uses the isolated database session.

"""

def get_session_override():

return session

# Override the application's dependency to use our test session

app.dependency_overrides[get_session] = get_session_override

client = TestClient(app)

yield client

# Clean up overrides after test

app.dependency_overrides.clear()Insight: The app.dependency_overrides feature is one of FastAPI’s most powerful capabilities for testing. It allows us to intercept the get_session call, which usually opens the file-based DB, and reroute it to our in-memory session fixture. This requires zero changes to the application code, ensuring we test the exact code that runs in production.

In tests/test_main.py, we write tests that describe the expected behavior of the API.

Python

from app.models import Hero

def test_create_hero(client):

"""Verify that a hero can be created and the ID is assigned."""

response = client.post(

"/heroes/",

json={"name": "Deadpond", "secret_name": "Dive Wilson"}

)

data = response.json()

assert response.status_code == 200

assert data["name"] == "Deadpond"

assert data["secret_name"] == "Dive Wilson"

assert data["id"] is not None

assert "age" in data and data["age"] is None

def test_read_heroes(session, client):

"""Verify that we can read back data inserted into the DB."""

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

session.add(hero_1)

session.commit()

response = client.get("/heroes/")

data = response.json()

assert response.status_code == 200

assert len(data) == 1

assert data["name"] == "Deadpond"

def test_create_hero_validation(client):

"""Verify that missing required fields trigger a 422 error."""

response = client.post(

"/heroes/",

json={"name": "Incomplete Hero"} # Missing secret_name

)

assert response.status_code == 422To run the suite:

Bash

uv run pytestThe output provides immediate feedback. This fast feedback loop (Edit -> Save -> Test) is the hallmark of a productive development environment.

Developing an API is only half the battle; the other half is deploying it reliably. In 2026, deployment typically implies containerization via Docker and orchestration via Kubernetes or serverless platforms (AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Run).

Building a Python application in a Docker image has been a complicated task in the past because of the issue of image size and caching. UV makes this much easier.

Dockerfile:

Dockerfile

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

FROM python:3.12-slim

# Install uv directly from the official image

COPY --from=ghcr.io/astral-sh/uv:latest /uv /bin/uv

WORKDIR /app

# Copy dependency definition first to leverage Docker layer caching

COPY pyproject.toml uv.lock./

# Install dependencies into the system environment

# --frozen ensures we use exact versions from lockfile

# --system installs into global Python, avoiding venv complexity in Docker

RUN uv sync --frozen --system

# Copy application code

COPY./app./app

# Run Uvicorn directly

CMD ["fastapi", "run", "app/main.py", "--port", "80", "--host", "0.0.0.0"]Key Optimizations:

For a production-grade API, several additional configurations are mandatory:

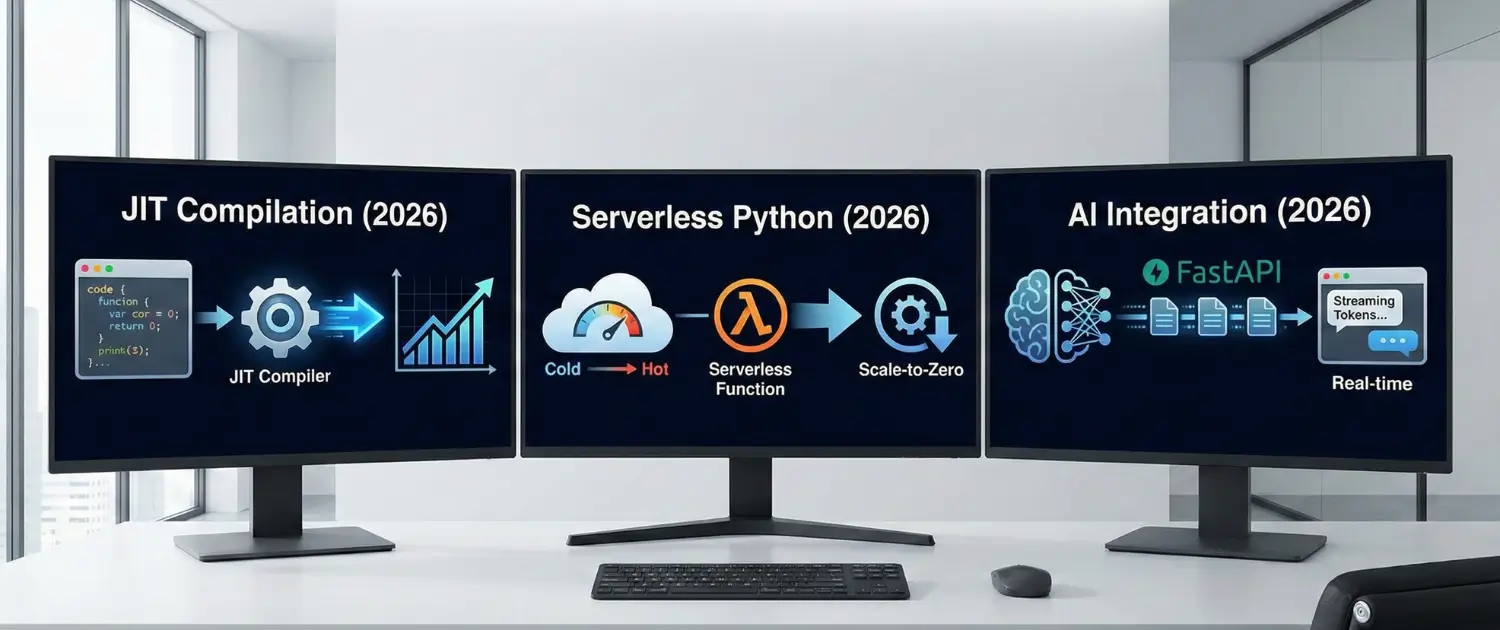

The Python API ecosystem is not static. Several trends are shaping the immediate future:

Hassan Tahir wrote this article, drawing on his experience to clarify WordPress concepts and enhance developer understanding. Through his work, he aims to help both beginners and professionals refine their skills and tackle WordPress projects with greater confidence.